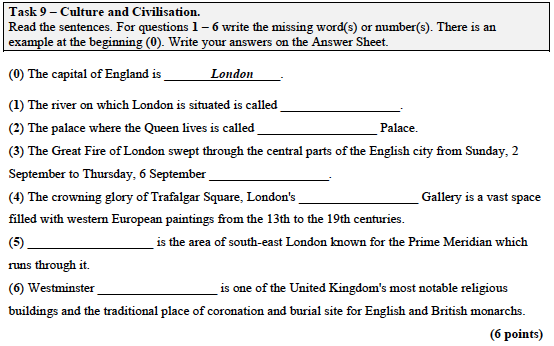

The year is 2020, and in the picture above you see a task in the national competition in English, in Croatia. The competition is held annually at three stages – school, county, and national. Those who rank high at the first level go to the next level and if they score well there they get invited to the national level. The competition is held for students in grade 8 of elementary school (age 14) and grades 2 and 4 in high school (ages 16 and 18). Students who rank high at the national level for the elementary school competition get extra points for enrolling into high school and those in high school get points for enrolling into university. So, we could call it a high-stakes test.

The school-level test consists of the usual reading comprehension tasks and use of language tasks (of which the task above is considered a part). The county-level test has also a listening task, and the national-level test has a writing and a speaking task.

The task above is from the elementary school test at the school level. What issues do I have with the task? (The whole test is a disaster, but I’ll just talk about this one task.)

1) After eight years of schooling, students’ intercultural competence is tested by a task that requires them to reproduce geographical and historical facts – and if that wasn’t bad enough, all six questions are about London. So, the message the student gets is – if you don’t know trivia about London, you’re not good at communicating in English. Not to mention that few actual residents of London would know the right answers to those questions.

2) English = United Kingdom. In Croatia, there are still teachers who will tell you that the ‘right’ version of English is British English and that it is this variety that our students should learn. Why? Because. This, of course, makes no sense if we look at the numbers. English is a first or an official language in a number of countries beyond the usual suspects (UK, US, Canada, and Australia), for example, the Philippines, Nigeria, Malta, India…, and there are three times more non-native than native speakers. So, no, teaching students about the cultures of the English-speaking world cannot come down to British culture alone, which is often the case in textbooks used in Croatia, where culture is understood as the sights of London, New York, and – if you’re lucky – a random Australian or Canadian location. And that’s what the textbooks covering a period of eight years of mandatory education revolve around. Culture coverage doesn’t get much better in high school.

3) Even if in some parallel universe you need to teach students only about British culture, intercultural competence is not about reproducing factual knowledge – it’s about using the language in a communicative act. Look at the task again. Where is communication in that? Or, if you don’t think this could be turned into a performance-based task, then let’s turn it into a critical thinking task and have students answer questions like ‘What did the lives of the natives look like after their countries were colonized by the British Empire?’, or an easier, factual one, ‘In which museum in London can you find the artifacts stolen from indigenous peoples during colonization?’

4) What is the washback effect of a task like this on the national competition? What will the teachers focus on in their classes to better prepare students for the next year’s competition? They will focus on memorizing trivia instead of developing (intercultural) communicative competence.

To sum up, having a task like this on a test in 2020 is unacceptable. We’ve been talking about communicative competence for forty years, English has grown immensely beyond its country of origin, in open society cultures intertwine and blend, and we have teachers testing students’ intercultural competence after eight years of schooling by asking them to reproduce facts about London. This is not what English language teaching is about.

Selected references:

Byram, M. (2008). From Foreign Language Education to Education for Intercultural Citizenship. Multilingual Matters.

Jandt, F. (2009). Intercultural Communication: Identities in a Global Community. Sage Publications.

Kramsch, C. (1993). Context and Culture in Language Teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Kukljanov, I.E. (2005). Principles of Intercultural Communication. Allyn and Bacon.

Moran, P. (2001). Teaching Culture: Perspectives in Practice. Heinle & Heinle.