Grammar Love

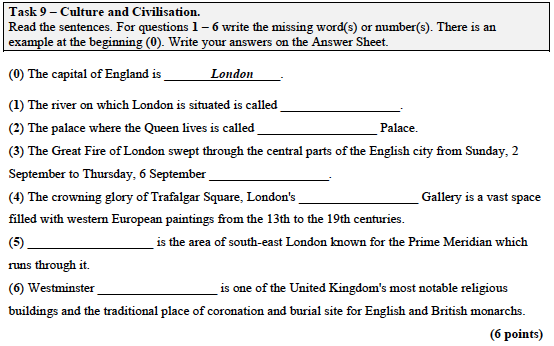

“We want grammar! We want grammar! We want grammar!”, the teachers rioted in the Facebook group for Croatian ELTs in elementary school, incited by the questions about grammar teaching and testing a couple of their peers posted mid-February 2021. “Who took their grammar?” you might wonder. Well, with the new Curriculum of English in 2019, the rubric “language use”, or grammar, disappeared from gradebooks, leaving four skills – listening, speaking, reading, and writing – as the sole elements to be graded. You can, of course, still assess grammar. If you want to give students a traditional grammar test, you can assess it formatively. If you want to test grammar summatively, that is, for a grade, you can (and should) do this by having grammar as an element in the criteria in the assessment of any of the four skills. Also, grammar can still be taught in any way it pleases the teacher (hopefully in a way that combines implicit and explicit instruction and the inductive and deductive approach). So, if you want to drill past simple into your students’ heads through mindless and decontextualized tasks, so be it. The curriculum developers’ rationale for assessing grammar primarily through the four skills was that students will undoubtedly have to show their grammatical competence (as well as other linguistic, sociolinguistic, and pragmatic competences) through these skills. This was and is, understandably, a tectonic change for numerous teachers, a paradigm shift if you will.

The main argument provided by the majority of teachers crying out for testing grammar is that students will not learn it unless it is graded. This is possibly the worst argument you can make. But let’s take a step back. When grammar was indeed an element in the gradebook, many teachers would proudly say that it is the most important element of all four or five, which thus carries the most weight when deciding on the students’ final grade. So this one element could drag your grade down in spite of the other three or four elements, which happened often as our students are pretty good at speaking English and not that bad in reading comprehension either. Thus, before 2019, teachers tested grammar vigorously – the majority of tests a student would take in a year were grammar tests – and final grades were in many cases primarily based on students’ grammatical competence.

Let us remind ourselves at this point that two of the most popular tests of English language proficiency, IELTS and TOEFL, which are widely used by universities across the world as a reliable and trustworthy indicator of a student’s competence in English, do not test grammar directly. In fact, these tests show what a student can do and understand in English. If such tests are good enough for Harvard and Cambridge, why aren’t they for our teachers? It’s not just the international tests. It’s the schools across the world that assess their students’ knowledge of foreign languages through the four skills: Denmark, Norway, Sweden, just to mention a few countries whose citizens rank high on the worldwide English proficiency index.

When some time ago I talked to my mentor about our teachers’ obsession with grammar, trying to understand where this need to test it incessantly comes from, she had one word to say: power. Grammar is power. We were taught by grammar-focused (if not grammar-obsessed) teachers, and many of us had to memorize Quirk by heart in university (I kid you not). We know grammar. We know how to explain the rules, we know how to make a grammar test, and we know how to grade a grammar test – which is probably the easiest and most straightforward thing to do when it comes to assessment. Grammar is power because we know the rules and students don’t. We feel at home with grammar. Grammar is our comfort zone, our go-to place. But you know what, grammar will not help you out there in the world, as I learned the hard way in the United States, Ireland, Kenya, Australia… What would’ve helped me was being more familiar with culture and the varieties of English. Grammar will rarely be the cause of a communication breakdown. In fact, studies with people from English-speaking countries have shown that what they find to be the most serious errors, that is, those that affect understanding the most, are lexical mistakes – not grammar mistakes. In other words, native speakers care more about word choice as opposed to grammar structures.

Let’s get back to that half-baked argument we left in the second paragraph. If your students don’t want to learn grammar because it’s not going to be on the graded test, then you have yourself a bigger problem, and that is your students’ motivation and their (mis)understanding of their roles in assessment. Saying that we should test grammar because otherwise it won’t be learnt is like saying we should give candy to kids when they’re being nice to each other, or otherwise they wouldn’t do it. Intrinsic motivation is key in many, many long-term efforts, and numerous studies have shown that this is the case with language learning as well. Extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, especially in the form of grades, has been shown to be detrimental to the development of competencies of different sorts. Just look at the flood of straight-A students in Croatia across all subjects – this happens because the students’ parents are focused on the numbers, and not on knowledge or skills. We need to move away from this, and not pander to it by saying that students will not learn what is not graded. The paradigm needs to change, and we’re the ones who have to do it. Motivating students is difficult, especially in high school, but it’s not impossible. There is a reason why teaching is one of the hardest jobs in the world – we need to be skilled at so many things that it often becomes too much to handle, so we fall back on what we know best, what takes little effort, and that is grammar and teaching to the textbook. I completely understand this – I’ve done it many a time. But if you think about it, teaching and testing grammar is so simple that a robot could replace you, not thirty years into the future, but today.

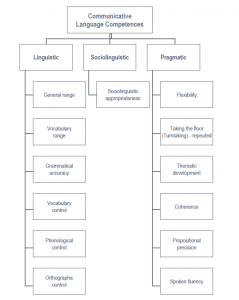

But let’s for a moment entertain the notion that grammar as an element needs to find its way back into the gradebook and become, as my friend would say, the fifth element. If you, dear reader, are of this opinion, may I ask you, what makes grammar deserve this special status in relation to the other twelve elements of communicative competence as outlined in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages Companion Volume (see Chart 1 below)? What is the criteria you use to justify that grammar of all these elements deserves to have its special rubric in the gradebook? If you have a good answer, then by all means, let’s bring grammar grades back.

Chart 1. Communicative language competences from Common European Framework of Reference for Languages Companion Volume with Descriptors (2018).

Designing communicatively-oriented tasks that target specific grammar items is no easy work. The endeavor is daunting, in fact. But it is daunting only if you are the only one doing it. Connecting with other teachers through ŽSV or HUPE, working as a team, would’ve made the whole thing much easier. Our group will make a communicatively oriented test for past simple, and yours will do it for future will. They’ll do it for passive, we’ll do it for the second conditional. Collaboration is key here, but it seems to be missing. Were you given sufficient training in designing communicatively-oriented tests? No. This is a major flaw in the system. But this doesn’t mean that we must immediately go back to how things were because no one spoonfed us the solutions. Going back would mean taking the path of least resistance.

Communicative competence is so much more than the knowledge of grammar. English is huge – all the varieties, all the cultures, so many stories to hear and read, so many songs to listen to and movies to watch, and discussions to have. And that is what counts – enabling students to connect with other people no matter where they come from. This is what English does. Being familiar with different customs, expressions, collocations, idioms will do wonders, while the ability to distinguish past simple from past perfect will matter little for the majority of our learners. They should still learn it, of course. And don’t worry, those who want to know more will still have to memorize Quirk in university.

If you disagree completely with what I wrote here, that’s okay – it’s not easy to let go of the past, especially if you remember it fondly. But I ask you to try to entertain, if only for a moment, the idea that despite all the challenges it is possible to do things differently and still get great results. That perhaps, after all, it is possible to teach English without putting a grade on a grammar test.

This text was published in HUPEzine in March 2021.